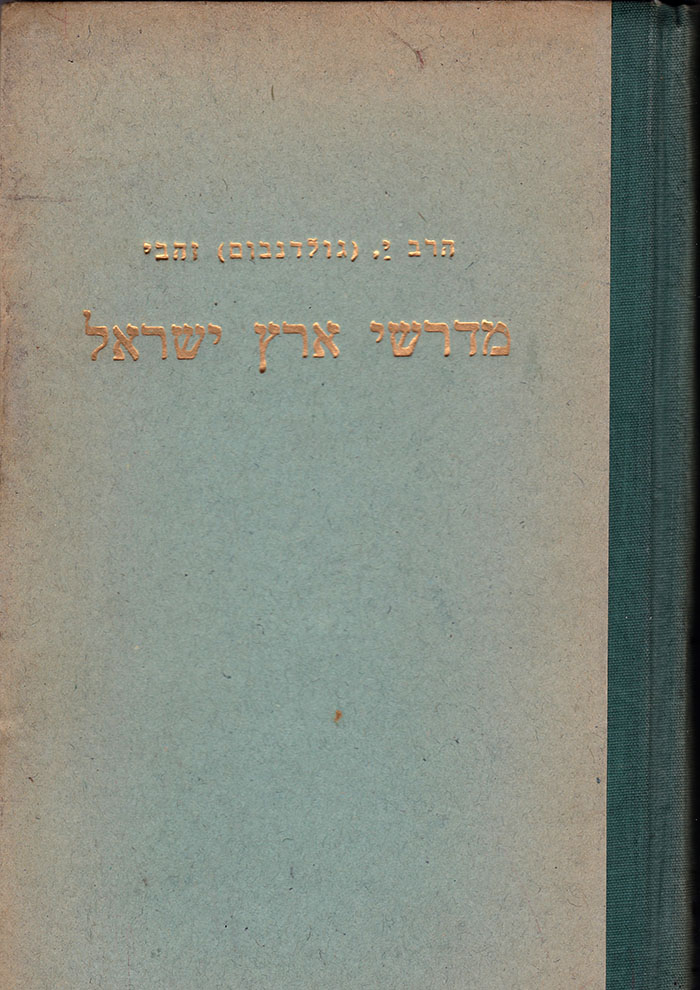

Midrash ha-Gadol Midrash Jonah Smaller midrashim. Finding Midrash on the shelf. Most individual works of midrash are shelved in BM 517. Collections of aggada (from the midrash and/or Talmud) are in BM 516 (including Sefer ha-Agadah and Ein Yaakov) Other translated collections are in BM 512 Books about Midrash are in BM 514.

| Rabbinic literature | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talmudic literature | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Halakhic Midrash | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Aggadic Midrash | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Targum | ||||||||

|

Midrash halakha (Hebrew: הֲלָכָה) was the ancient Judaicrabbinic method of Torah study that expounded upon the traditionally received 613 Mitzvot (commandments) by identifying their sources in the Hebrew Bible, and by interpreting these passages as proofs of the laws' authenticity. Midrash more generally also refers to the non-legal interpretation of the Tanakh (aggadic midrash). The term is applied also to the derivation of new laws, either by means of a correct interpretation of the obvious meaning of scriptural words themselves or by the application of certain hermeneutic rules.

The Midrashim are mostly derived from, and based upon, the teachings of the Tannaim.

- 2Types of midrash

Terminology[edit]

The phrase 'Midrash halakha' was first employed by Nachman Krochmal,[1] the Talmudic expression being 'Midrash Torah' = 'investigation of the Torah'.[2] These interpretations were often regarded as corresponding to the real meaning of the Scriptural texts; thus it was held that a correct elucidation of the Torah carried with it the proof of the halakha and the reason for its existence.

Types of midrash[edit]

In the Midrash halakha three divisions may be distinguished:

- The midrash of the older halakha, that is, the midrash of the Soferim and the Tannaim of the first two generations;

- The midrash of the younger halakha, or the midrash of the Tannaim of the three following generations;

- The midrash of several younger tannaim and of many amoraim who did not interpret a Biblical passage as an actual proof of the halakha, but merely as a suggestion or a support for it ('zekher le-davar'; 'asmakhta').

The Midrash of the older halakha[edit]

The older halakha sought only to define the compass and scope of individual laws, asking under what circumstances of practical life a given rule was to be applied and what would be its consequences. The older Midrash, therefore, aims at an exact definition of the laws contained in the Scriptures by an accurate interpretation of the text and a correct determination of the meaning of the various words. The form of exegesis adopted is frequently one of simple lexicography, and is remarkably brief.

A few examples will serve to illustrate the style of the older Midrash halakha. It translates the word 'ra'ah' (Exodus 21:8) 'displease' (Mekhilta, Mishpatim), which is contrary to the interpretation of Rabbi Eliezer. From the expression 'be-miksat' (Exodus 12:4), which, according to it, can mean only 'number,' the older halakha deduces the rule that when killing the Passover lamb the slaughterer must be aware of the number of persons who are about to partake of it.[3]

The statement that the determination of the calendar of feasts depends wholly on the decision of the nasi and his council is derived from Leviticus 23:37, the defectively written 'otam' (them) being read as 'attem' (you) and the interpretation, 'which you shall proclaim,' being regarded as conforming to the original meaning of the phrase.[4] When two different forms of the same word in a given passage have been transmitted, one written in the text (ketib), and the other being the traditional reading (qere), the halakha, not wishing to designate either as wrong, interprets the word in such a way that both forms may be regarded as correct. Thus it explains Leviticus 25:30-where according to the qere the meaning is 'in the walled city,' but according to the ketib, 'in the city that is not walled'-as referring to a city that once had walls, but no longer has them.[5] In a similar way it explains Leviticus 11:29.[6] According to Krochmal,[7] the ketib was due to the Soferim themselves, who desired that the interpretation given by the halakha might be contained in the text; for example, in the case of 'otam' and 'attem' noted above, they intentionally omitted the letter vav.

| Rabbinical eras |

|---|

|

The Midrash of the younger halakha[edit]

The younger halakha did not confine itself to the mere literal meaning of single passages, but sought to draw conclusions from the wording of the texts in question by logical deductions, by combinations with other passages, etc. Hence its midrash differs from the simple exegesis of the older halakha. It treats the Bible according to certain general principles, which in the course of time became more and more amplified and developed (see Talmud); and its interpretations depart further and further from the simple meaning of the words.

A few examples will illustrate this difference in the method of interpretation between the older and the younger halakhah. It was a generally accepted opinion that the first Passover celebrated in Egypt, that of the Exodus, differed from those that followed it, in that at the first one the prohibition of leavened bread was for a single day only, whereas at subsequent Passovers this restriction extended to seven days. The older halakha[8] represented by R. Jose the Galilean, bases its interpretation on a different division of the sentences in Exodus 13 than the one generally received; connecting the word 'ha-yom' (= 'this day', the first word of verse 13:4) with verse 13:3 and so making the passage read: 'There shall no leavened bread be eaten this day.' The younger halakha reads 'ha-yom' with verse 13:4, and finds its support for the traditional halakha by means of the principle of 'semukot' (collocation); that is to say, the two sentences, 'There shall no leavened bread be eaten,' and 'This day came ye out,' though they are separated grammatically, are immediately contiguous in the text, and exert an influence over each other.[9] What the older halakha regarded as the obvious meaning of the words of the text, the younger infers from the collocation of the sentences.

The wide divergence between the simple exegesis of the older halakha and the artificiality of the younger is illustrated also by the difference in the method of explaining the Law, cited above, in regard to uncleanness. Both halakhot regard it as self-evident that if a man is unclean, whether it be from contact with a corpse or from any other cause, he may not share in the Passover.[10] The younger halakha, despite the dot over the ה, reads 'rechokah' and makes it refer to 'derekh' ('road' or 'way') even determining how far away one must be to be excluded from participation in the feast. However, to find a ground for the halakha that those who are unclean through contact with other objects than a corpse may have no share in the Passover, it explains the repetition of the word 'ish' in this passage (Leviticus 9 10) as intending to include all other cases of defilement.

Despite this difference in method, the midrashim of the older and of the younger halakha alike believed that they had sought only the true meaning of the Scriptures. Their interpretations and deductions appeared to them to be really contained in the text; and they wished them to be considered correct Biblical expositions. Hence they both have the form of Scriptural exegesis, in that each mentions the Biblical passage and the halakha that explains it, or, more correctly, derives from it.

Abstract and Midrash halakha[edit]

It is to a law stated in this form—i.e., together with the Biblical passage it derives from—that the name midrash applies, whereas one that, though ultimately based on the Bible, is cited independently as an established statute is called a halakha. Collections of halakhot of the second sort are the Mishnah and the Tosefta; compilations of the first sort are the halakhic midrashim. This name they receive to distinguish them from the haggadic midrashim, since they contain halakhot for the most part, although there are haggadic portions in them. In these collections the line between independent halakha and Midrash halakha is not sharply drawn.

Many mishnayot (single paragraph units) in the Mishnah and in the Tosefta are midrashic halakhot.[11] On the other hand, the halakhic midrashim contain independent halakhot without statements of their Scriptural bases.[12] This confusion is explained by the fact that the redactors of the two forms of halakhot borrowed passages from one another.[13]

The schools of R. Akiva and R' Ishmael[edit]

Since the halakhic Midrashim had for their secondary purpose the exegesis of the Bible, they were arranged according to the text of the Pentateuch. As Genesis contains very little matter of a legal character, there was probably no halakhic midrash to this book. On the other hand, to each of the other four books of the Pentateuch there was a midrash from the school of R. Akiva and one from the school of R. Ishmael, and these midrashim are still in great part extant. The halakhic midrash to Exodus from the school of R. Ishmael is the Mekilta, while that of the school of R. Akiva is the Mekilta of R. Shimon bar Yochai, most of which is contained in Midrash ha-Gadol.[14]

A halakhic midrash to Leviticus from the school of R. Akiva exists under the name 'Sifra' or 'Torat Kohanim.' There was one to Leviticus from the school of R. Ishmael also, of which only fragments have been preserved.[15] The halakhic midrash to Numbers from the school of R. Ishmael is the 'Sifre'; while of that of the school of R. Akiva, the Sifre Zutta, only extracts have survived in Yalkut Shimoni and Midrash ha-Gadol.[16] The middle portion of the Sifre to Deuteronomy forms a halakhic midrash on that book from the school of R. Akiva, while another from the school of R. Ishmael has been shown by Hoffmann to have existed.[17] This assignment of the several midrashim to the school of R. Ishmael and to that of R. Akiva respectively, however, is not to be too rigidly insisted upon; for the Sifre repeats in an abbreviated form some of the teachings of the Mekilta, just as the Mekilta included in the Midrash ha-Gadol has incorporated many doctrines from Akiba's midrash.[18]

Midrashic halakhot found also scattered through the two Talmuds; for many halakhic baraitot (traditions in oral law) that occur in the Talmuds are really midrashic, recognizable by the fact that they mention the Scriptural bases for the respective halakhot, often citing the text at the very beginning. In the Jerusalem Talmud the midrashic baraitot frequently begin with 'Ketib' (= 'It is written'), followed by the Scriptural passage. From the instances of midrashic baraitot in the Talmud that are not found in the extant midrashim, the loss of many of the latter class of works must be inferred.[19]

The Midrash of Several Younger Tannaim and of many Amoraim[edit]

The Midrash which the Amoraim use when deducing tannaitic halakhot from the Scriptures is frequently very distant from the literal meaning of the words. The same is true of many explanations by the younger tannaim. These occur chiefly as expositions of such halakhot as were not based on Scripture but which it was desired to connect with or support by a word in the Bible. The Talmud often says of the interpretations of a baraita: 'The Biblical passage should be merely a support' (asmachta). Of this class are many of the explanations in the Sifra[20] and in the Sifre.[21] The tanna also often says frankly that he does not cite the Biblical word as proof ('re'aya'), but as a mere suggestion ('zecher'; lit. 'reminder') of the halakah, or as an allusion ('remez') to it.[22]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^In his 'Moreh Nebuke ha-Zeman,' p. 163

- ^Kiddushin 49b

- ^Mekhilta Bo 3 [ed. I.H. Weiss, p. 5a]

- ^Rosh Hashana 25a

- ^Arachin 32b

- ^Hullin 65a

- ^l.c. pp. 151 et seq.

- ^In Mekhilta Bo, 16 [ed. Weiss, 24a]

- ^Pesachim 28b, 96b

- ^Pesachim 93a

- ^e.g., Berachot 1:3,5; Bekhorot 1:4,7; Hullin 2:3,8:4; Tosefta Zevachim 1:8, 12:20

- ^e.g. Sifra Vayikra Hovah 1:9-13 (ed. Weiss, p. 16a, b).

- ^Hoffmann, 'Zur Einleitung in die Halach. Midraschim,' p. 3

- ^Compare I. Lewy, 'Ein Wort über die Mechilta des R. Simon,' Breslau, 1889

- ^Compare Hoffmann, l.c. pp. 72-77

- ^Compare ib. pp. 56-66

- ^D. Hoffmann, 'Liḳḳuṭe Mekilta, Collectaneen aus einer Mechilta zu Deuteronomium,' in 'Jubelschrift zum 70. Geburtstag des Dr. I. Hildesheimer,' Hebrew part, pp. 1-32, Berlin, 1890; idem, 'Ueber eine Mechilta zu Deuteronomium,' ib. German part, pp. 83-98; idem, 'Neue Collectaneen,' etc., 1899

- ^Compare Hoffmann, l.c. p. 93

- ^Hoffmann, 'Zur Einleitung,' p. 3

- ^Compare Tosafot Bava Batra 66a, s.v. 'miklal'

- ^Compare Tosafot Bekhorot 54a, s.v. 'ushne'

- ^Mekhilta Bo 5 [ed. Weiss, p. 7b]; Sifre Numbers 112, 116 [ed. Friedmann, pp. 33a, 36a]

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). 'MIDRASH HALAKAH'. The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.Bibliography:

- Z. Frankel, Hodegetica in Mischnam, pp. 11-18, 307-314, Leipsic, 1859;

- A. Geiger, Urschrift, pp. 170-197, Breslau, 1857;

- D. Hoffmann, Zur Einleitung in die Halachischen Midraschim, Berlin, 1888;

- Nachman Krochmal, Moreh Nebuke ha-Zeman, section 13, pp. 143-183, Lemberg, 1863;

- H. M. Pineles, Darkah shel Torah, pp. 168-201, Vienna, 1861;

- I. H. Weiss, Dor, i. 68-70 et passim, ii. 42-53.

Further reading[edit]

- Jay M. Harris, Midrash Halachah, in: The Cambridge History of Judaism, Volume IV: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period. Cambridge University Press (2006).

Midrash (/ˈmɪdrɑːʃ/;[1]Hebrew: מִדְרָשׁ; pl. Hebrew: מִדְרָשִׁיםmidrashim) is biblicalexegesis by ancient Judaic authorities,[2] using a mode of interpretation prominent in the Talmud.

Midrash and rabbinic readings 'discern value in texts, words, and letters, as potential revelatory spaces,' writes the Hebrew scholar Wilda C. Gafney. 'They reimagine dominant narratival readings while crafting new ones to stand alongside—not replace—former readings. Midrash also asks questions of the text; sometimes it provides answers, sometimes it leaves the reader to answer the questions.'[3]

Vanessa Lovelace defines midrash as 'a Jewish mode of interpretation that not only engages the words of the text, behind the text, and beyond the text, but also focuses on each letter, and the words left unsaid by each line.'[4]

Midrash In English Online

The term is also used of a rabbinic work that interprets Scripture in that manner.[5][6] Such works contain early interpretations and commentaries on the Written Torah and Oral Torah (spoken law and sermons), as well as non-legalistic rabbinic literature (haggadah) and occasionally Jewish religious laws (halakha), which usually form a running commentary on specific passages in the Hebrew Scripture (Tanakh).[7]

'Midrash', especially if capitalized, can refer to a specific compilation of these rabbinic writings composed between 400 and 1200 CE.[1][8]

According to Gary Porson and Jacob Neusner, 'midrash' has three technical meanings: 1) Judaic biblical interpretation; 2) the method used in interpreting; 3) a collection of such interpretations.[9]

- 4Jewish midrashic literature

- 5Classical compilations

Etymology[edit]

| Part of a series on the | ||

| Bible | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Bible bookBible portal |

The Hebrew word midrash is derived from the root of the verb darash (דָּרַשׁ), which means 'resort to, seek, seek with care, enquire, require',[10] forms of which appear frequently in the Bible.[11]

The word midrash occurs twice in the Hebrew Bible: 2 Chronicles 13:22 'in the midrash of the prophet Iddo', and 24:27 'in the midrash of the book of the kings'. KJV and ESV translate the word as 'story' in both instances; the Septuagint translates it as βιβλίον (book) in the first, as γραφή (writing) in the second. The meaning of the Hebrew word in these contexts is uncertain: it has been interpreted as referring to 'a body of authoritative narratives, or interpretations thereof, concerning historically important figures'[12] and seems to refer to a 'book', perhaps even a 'book of interpretation', which might make its use a foreshadowing of the technical sense that the rabbis later gave to the word.[13]

Since the early Middle Ages the function of much of midrashic interpretation has been distinguished from that of peshat, straight or direct interpretation aiming at the original literal meaning of a scriptural text.[12]

Midrash as genre[edit]

A definition of 'midrash' repeatedly quoted by other scholars[14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22] is that given by Gary G. Porton in 1981: 'a type of literature, oral or written, which stands in direct relationship to a fixed, canonical text, considered to be the authoritative and revealed word of God by the midrashist and his audience, and in which this canonical text is explicitly cited or clearly alluded to'.[23]

Lieve M. Teugels, who would limit midrash to rabbinic literature, offered a definition of midrash as 'rabbinic interpretation of Scripture that bears the lemmatic form',[21] a definition that, unlike Porton's, has not been adopted by others. While some scholars agree with the limitation of the term 'midrash' to rabbinic writings, others apply it also to certain Qumran writings,[24][25] to parts of the New Testament,[26][27][28] and of the Hebrew Bible (in particular the superscriptions of the Psalms, Deuteronomy, and Chronicles),[29] and even modern compositions are called midrashim.[30][31]

Midrash as method[edit]

Midrash is now viewed more as method than genre, although the rabbinic midrashim do constitute a distinct literary genre.[32][33]

According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, 'Midrash was initially a philological method of interpreting the literal meaning of biblical texts. In time it developed into a sophisticated interpretive system that reconciled apparent biblical contradictions, established the scriptural basis of new laws, and enriched biblical content with new meaning. Midrashic creativity reached its peak in the schools of Rabbi Ishmael and Akiba, where two different hermeneutic methods were applied. The first was primarily logically oriented, making inferences based upon similarity of content and analogy. The second rested largely upon textual scrutiny, assuming that words and letters that seem superfluous teach something not openly stated in the text.'[34]

Many different exegetical methods are employed in an effort to derive deeper meaning from a text. This is not limited to the traditional thirteen textual tools attributed to the TannaRabbi Ishmael, which are used in the interpretation of halakha (Jewish law). The presence of words or letters which are seen to be apparently superfluous, and the chronology of events, parallel narratives or what are seen as other textual 'anomalies' are often used as a springboard for interpretation of segments of Biblical text. In many cases, a handful of lines in the Biblical narrative may become a long philosophical discussion

Jacob Neusner distinguishes three midrash processes:

- paraphrase: recounting the content of the biblical text in different language that may change the sense;

- prophecy: reading the text as an account of something happening or about to happen in the interpreter's time;

- parable or allegory: indicating deeper meanings of the words of the text as speaking of something other than the superficial meaning of the words or of everyday reality, as when the love of man and woman in the Song of Songs is interpreted as referring to the love between God and Israel or the Church as in Isaiah 5:1-6 and in the New Testament.[35]

Jewish midrashic literature[edit]

Numerous Jewish midrashim previously preserved in manuscript form have been published in print, including those denominated as smaller[36] or minor midrashim. Bernard H. Mehlman and Seth M. Limmer deprecate this usage on the grounds that the term 'minor' seems judgmental and 'small' is inappropriate for midrashim some of which are lengthy. They propose instead the term 'medieval midrashim', since the period of their production extended from the twilight of the rabbinic age to the dawn of the Age of Enlightenment.[37]

Generally speaking, rabbinic midrashim either focus on religious law and practice (halakha) or interpret biblical narrative in relation to non-legal ethics or theology, creating homilies and parables based on the text. In the latter case they are described as aggadic.[38]

Halakhic midrashim[edit]

| Rabbinic literature | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

'Talmud Readers' by Adolf Behrman | ||||||||

| Talmudic literature | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Halakhic Midrash | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Aggadic Midrash | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Targum | ||||||||

|

Midrash halakha is the name given to a group of tannaitic expositions on the first four books of the Hebrew Bible.[39] These midrashim, written in Mishnahic Hebrew, clearly distinguish between the Biblical texts that they discuss, and the rabbinic interpretation of that text. They often go well beyond simple interpretation and derive or provide support for halakha. This work is based on pre-set assumptions about the sacred and divine nature of the text, and the belief in the legitimacy that accords with rabbinic interpretation.[40]

Although this material treats the biblical texts as the authoritative word of God, it is clear that not all of the Hebrew Bible was fixed in its wording at this time, as some verses that are cited differ from the Masoretic, and accord with the Septuagint, or Samaritan Torah instead.[41]

Origins[edit]

With the growing canonization of the contents of the Hebrew Bible, both in terms of the books that it contained, and the version of the text in them, and an acceptance that new texts could not be added, there came a need to produce material that would clearly differentiate between that text, and rabbinic interpretation of it. By collecting and compiling these thoughts they could be presented in a manner which helped to refute claims that they were only human interpretations. The argument being that by presenting the various collections of different schools of thought each of which relied upon close study of the text, the growing difference between early biblical law, and its later rabbinic interpretation could be reconciled.[40]

Aggadic midrashim[edit]

Midrashim that seek to explain the non-legal portions of the Hebrew Bible are sometimes referred to as aggadah or haggadah.[42]

Aggadic discussions of the non-legal parts of Scripture are characterized by a much greater freedom of exposition than the halakhic midrashim (midrashim on Jewish law). Aggadic expositors availed themselves of various techniques, including sayings of prominent rabbis. These aggadic explanations could be philosophical or mystical disquisitions concerning angels, demons, paradise, hell, the messiah, Satan, feasts and fasts, parables, legends, satirical assaults on those who practice idolatry, etc.

Some of these midrashim entail mystical teachings. The presentation is such that the midrash is a simple lesson to the uninitiated, and a direct allusion, or analogy, to a mystical teaching for those educated in this area.

An example of a midrashic interpretation:

- 'And God saw all that He had made, and found it very good. And there was evening, and there was morning, the sixth day.' (Genesis 1:31)—Midrash: Rabbi Nahman said in Rabbi Samuel's name: 'Behold, it was very good' refers to the Good Desire; 'AND behold, it was very good' refers to the Evil Desire. Can then the Evil Desire be very good? That would be extraordinary! But without the Evil Desire, however, no man would build a house, take a wife and beget children; and thus said Solomon: 'Again, I considered all labour and all excelling in work, that it is a man's rivalry with his neighbour.' (Kohelet IV, 4).[43]

Classical compilations[edit]

| Rabbinical eras |

|---|

|

Tannaitic[edit]

- Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva. This book is a midrash on the names of the letters of the hebrew alphabet.

- Mekhilta. The Mekhilta essentially functions as a commentary on the Book of Exodus. There are two versions of this midrash collection. One is Mekhilta de Rabbi Ishmael, the other is Mekhilta de Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai. The former is still studied today, while the latter was used by many medieval Jewish authorities. While the latter (bar Yohai) text was popularly circulated in manuscript form from the 11th to 16th centuries, it was lost for all practical purposes until it was rediscovered and printed in the 19th century.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael. This is a halakhic commentary on Exodus, concentrating on the legal sections, from Exodus 12 to 35. It derives halakha from Biblical verses. This midrash collection was redacted into its final form around the 3rd or 4th century; its contents indicate that its sources are some of the oldest midrashim, dating back possibly to the time of Rabbi Akiva. The midrash on Exodus that was known to the Amoraim is not the same as our current mekhilta; their version was only the core of what later grew into the present form.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Shimon. Based on the same core material as Mekhilta de Rabbi Ishmael, it followed a second route of commentary and editing, and eventually emerged as a distinct work. The Mekhilta de Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai is an exegetical midrash on Exodus 3 to 35, and is very roughly dated to near the 4th century.

- Seder Olam Rabbah (or simply Seder Olam). Traditionally attributed to the Tannaitic Rabbi Yose ben Halafta. This work covers topics from the creation of the universe to the construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem.

- Sifra on Leviticus. The Sifra work follows the tradition of Rabbi Akiva with additions from the School of Rabbi Ishmael. References in the Talmud to the Sifra are ambiguous; It is uncertain whether the texts mentioned in the Talmud are to an earlier version of our Sifra, or to the sources that the Sifra also drew upon. References to the Sifra from the time of the early medieval rabbis (and after) are to the text extant today. The core of this text developed in the mid-3rd century as a critique and commentary of the Mishnah, although subsequent additions and editing went on for some time afterwards.

- Sifre on Numbers and Deuteronomy, going back mainly to the schools of the same two Rabbis. This work is mainly a halakhic midrash, yet includes a long haggadic piece in sections 78-106. References in the Talmud, and in the later Geonic literature, indicate that the original core of Sifre was on the Book of Numbers, Exodus and Deuteronomy. However, transmission of the text was imperfect, and by the Middle Ages, only the commentary on Numbers and Deuteronomy remained. The core material was redacted around the middle of the 3rd century.

- Sifre Zutta (The small Sifre). This work is a halakhic commentary on the book of Numbers. The text of this midrash is only partially preserved in medieval works, while other portions were discovered by Solomon Schechter in his research in the famed Cairo Geniza. It seems to be older than most other midrash, coming from the early 3rd century.

Post-Talmudic[edit]

- Midrash Qohelet, on Ecclesiastes (probably before middle of 9th century).

- Midrash Esther, on Esther (940 CE).

- The Pesikta, a compilation of homilies on special Pentateuchal and Prophetic lessons (early 8th century), in two versions:

- Pirqe Rabbi Eliezer (not before 8th century), a midrashic narrative of the more important events of the Pentateuch.

- Tanchuma or Yelammedenu (9th century) on the whole Pentateuch; its homilies often consist of a halakhic introduction, followed by several poems, exposition of the opening verses, and the Messianic conclusion. There are actually a number of different Midrash Tanhuma collections. The two most important are Midrash Tanhuma Ha Nidpas, literally the published text. This is also sometimes referred to as Midrash Tanhuma Yelamdenu. The other is based on a manuscript published by Solomon Buber and is usually known as Midrash Tanhuma Buber, much to many students' confusion, this too is sometimes referred to as Midrash Tanhuma Yelamdenu. Although the first is the one most widely distributed today, when the medieval authors refer to Midrash Tanchuma, they usually mean the second.

- Midrash Shmuel, on the first two Books of Kings (I, II Samuel).

- Midrash Tehillim, on the Psalms.

- Midrash Mishlé, a commentary on the book of Proverbs.

- Yalkut Shimoni. A collection of midrash on the entire Hebrew Scriptures (Tanakh) containing both halakhic and aggadic midrash. It was compiled by Shimon ha-Darshan in the 13th century CE and is collected from over 50 other midrashic works.

- Midrash HaGadol (in english: the great midrash) (in hebrew: מדרש הגדול) was written by Rabbi David Adani of Yemen (14th century).It is a compilation of aggadic midrashim on the Pentateuch taken from the two Talmuds and earlier Midrashim of Yemenite provenance.

- Tanna Devei Eliyahu. This work that stresses the reasons underlying the commandments, the importance of knowing Torah, prayer, and repentance, and the ethical and religious values that are learned through the Bible. It consists of two sections, Seder Eliyahu Rabbah and Seder Eliyahu Zuta. It is not a compilation but a uniform work with a single author.

- Midrash Tadshe (also called Baraita de-Rabbi Pinehas ben Yair):

Midrash Rabbah Online English

Midrash Rabbah[edit]

- Midrash Rabbah — widely studied are the Rabboth (great commentaries), a collection of ten midrashim on different books of the Bible (namely, the five books of the Torah and the Five Scrolls). Although referred to collectively as the Midrash Rabbah, they are not a cohesive work, being written by different authors in different locales in different historical eras. The ones on Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy are chiefly made up of homilies on the Scripture sections for the Sabbath or festival, while the others are rather of an exegetical nature.

- Bereshith Rabba, Genesis Rabbah. This text dates from the sixth century. A midrash on Genesis, it offers explanations of words and sentences and haggadic interpretations and expositions, many of which are only loosely tied to the text. It is often interlaced with maxims and parables. Its redactor drew upon earlier rabbinic sources, including the Mishnah, Tosefta, the halakhic midrashim the Targums. It apparently drew upon a version of Talmud Yerushalmi that resembles, yet was not identical to, the text that survived to present times. It was redacted sometime in the early fifth century.

- Shemot Rabba, Exodus Rabbah (tenth or eleventh and twelfth century)

- Vayyiqra Rabba, Leviticus Rabbah (middle seventh century)

- Bamidbar Rabba, Numbers Rabbah (twelfth century)

- Devarim Rabba, Deuteronomy Rabbah (tenth century)

- Shir Hashirim Rabba, Song of Songs Rabbah (probably before the middle of ninth century)

- Ruth Rabba, (probably before the middle of ninth century)

- Eicha Rabba, Lamentations Rabbah (seventh century). Lamentations Rabbah has been transmitted in two versions. One edition is represented by the first printed edition (at Pesaro in 1519); the other is the Salomon Buber edition, based on manuscript J.I.4 from the Biblioteca Casanatense in Rome. This latter version (Buber's) is quoted by the Shulkhan Arukh, as well as medieval Jewish authorities. It was probably redacted sometime in the fifth century.

Contemporary Jewish midrash[edit]

A wealth of literature and artwork has been created in the 20th and 21st centuries by people aspiring to create 'contemporary midrash'. Forms include poetry, prose, Bibliodrama (the acting out of Bible stories), murals, masks, and music, among others. The Institute for Contemporary Midrash was formed to facilitate these reinterpretations of sacred texts. The institute hosted several week-long intensives between 1995 and 2004, and published eight issues of Living Text: The Journal of Contemporary Midrash from 1997 to 2000.

Contemporary views[edit]

According to Carol Bakhos, recent studies that use literary-critical tools to concentrate on the cultural and literary aspects of midrash have led to a rediscovery of the importance of these texts for finding insights into the rabbinic culture that created them. Midrash is increasingly seen as a literary and cultural construction, responsive to literary means of analysis.[44]

Reverend Wilda C. Gafney has coined and expanded on womanist midrash, a particular practice and method that Gafney defines as:

'[...] A set of interpretive practices, including translation, exegesis, and biblical narratives, that attends to marginalized characters in biblical narratives, specially women and girls, intentionally including and centering on non-Israelite peoples and enslaved persons. Womanist midrash listens to and for their voices in and through the Hebrew Bible, while acknowledging that often the text does not speak, or even intend to speak, to or for them, let alone hear them. In the tradition of rabbinic midrash and contemporary feminist biblical scholarship, womanist midrash offers names for anonymized characters and crafts/listens to/gives voice to those characters.'[45]

Gafney's analysis also draws parallels between midrash as a Jewish exegetical practice and African American Christian practices of biblical interpretation, wherein both practices privilege 'sacred imaginative interrogation,' or 'sanctified imagination' as it is referred to in the black preaching tradition, when exegeting and interpreting the text. 'Like classical and contemporary Jewish midrash, the sacred imagination [as practiced in black preaching traditions] tells us the story behind the story, the story between the lines on the page,' Gafney writes.[46][4]

Frank Kermode has written that midrash is an imaginative way of 'updating, enhancing, augmenting, explaining, and justifying the sacred text'. Because the Tanakh came to be seen as unintelligible or even offensive, midrash could be used as a means of rewriting it in a way that both makes it more acceptable to later ethical standards and renders it less obviously implausible.[47]

James L. Kugel, in The Bible as It Was (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997), examines a number of early Jewish and Christian texts that comment on, expand, or re-interpret passages from the first five books of the Tanakh between the third century BCE and the second century CE.

Kugel traces how and why biblical interpreters produced new meanings by the use of exegesis on ambiguities, syntactical details, unusual or awkward vocabulary, repetitions, etc. in the text. As an example, Kugel examines the different ways in which the biblical story that God's instructions are not to be found in heaven (Deut 30:12) has been interpreted. Baruch 3:29-4:1 states that this means that divine wisdom is not available anywhere other than in the Torah. Targum Neophyti (Deut 30:12) and b. Baba Metzia 59b claim that this text means that Torah is no longer hidden away, but has been given to humans who are then responsible for following it.[48]

See also[edit]

- Midrasz, a Polish language journal on Polish Jewish matters

References[edit]

- ^ ab'midrash'. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^Jacob Neusner, What Is Midrash (Wipf and Stock 2014), p. xi

- ^1966-, Gafney, Wilda. Womanist Midrash : a reintroduction to the women of the Torah and the throne (First ed.). Louisville, Kentucky. ISBN9780664239039. OCLC988864539.

- ^ abLovelace, Vanessa (2018-09-11). 'Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne, written by Wilda C. Gafney'. Horizons in Biblical Theology. 40 (2): 212–215. doi:10.1163/18712207-12341379. ISSN0195-9085.

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica: Midrash

- ^Jewish Encyclopedia (1906): 'Midrashim, Smaller'

- ^ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA, Second Edition, Volume 14, pg 182, Moshe David Herr

- ^Collins English Dictionary

- ^Chan Man Ki, 'A Comparative Study of Jewish Commentaries and Patristic Literature on the Book of Ruth' (University of Pretoria 2010), p. 112, citing Gary G. Porton, 'Rabbinic Midrash' in Jacob Neusner, Judaism in Late Antiquity Vol. 1, p. 217; and Jacob Neusner, Questions and Answers: Intellectual Foundations of Judaism (Hendrickson 2005), p. 41

- ^Old Testament Hebrew Lexicon: Darash

- ^Brown–Driver–Briggs: 1875. darash

- ^ abThe Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion (Oxford University Press 2011): 'Midrash and midrashic literature'

- ^Lieve M. Teugels, Bible and Midrash: The Story of 'The Wooing of Rebekah' (Gen. 24) (Peeters 2004), p. 162

- ^Paul D. Mandel, The Origins of Midrash: From Teaching to Text (BRILL 2017), p. 16

- ^Jacob Neusner, What Is Midrash? (Wipf and Stock 2014), p. 9

- ^Lidija Novaković, 'The Scriptures and Scriptural Interpretation' in Joel B. Green, Lee Martin McDonald (editors), The World of the New Testament: Cultural, Social, and Historical Contexts (Baker Academic 2013)

- ^Martin McNamara, Targum and New Testament: Collected Essays (Mohr Siebeck 2011), p. 417

- ^Carol Bakhos, Current Trends in the Study of Midrash (BRILL 2006), p. 163

- ^Andrew Lincoln, Hebrews: A Guide (Bloomsbury 2006), p. 71

- ^Adam Nathan Chalom, Modern Midrash: Jewish Identity and Literary Creativity (University of Michigan 2005), pp. 42 and 83

- ^ abLieve M. Teugels, Bible and Midrash: The Story of 'The Wooing of Rebekah' (Gen. 24) (Peeters 2004), p. 168

- ^Jacob Neusner, Midrash as Literature: The Primacy of Discourse (Wipf and Stock 2003), p. 3

- ^Gary G. Porton, 'Defining Midrash' in Jacob Neusner (editor), The Study of Ancient Judaism: Mishnah, Midrash, Siddur (KTAV 1981), pp. 59−92

- ^Matthias Henze, Biblical Interpretation at Qumran (Eerdmans 2005), p. 86

- ^Hartmut Stegemann, The Library of Qumran: On the Essenes, Qumran, John the Baptist, and Jesus (BRILL 1998)

- ^Craig A. Evans, 'Listening for Echoes of Interpreted Scripture' in Craig A. Evans, James A. Sanders (editors), Paul and the Scriptures of Israel (Bloomsbury 2015), p. 50

- ^George Wesley Buchanan, The Gospel of Matthew (Wipf and Stock 2006), p. 644 (vol. 2)

- ^Stanley E. Porter, Dictionary of Biblical Criticism and Interpretation (Routledge 2007), p. 226

- ^Timothy H. Lim, 'The Origins and Emergence of Midrash in Relation to the Hebrew Scriptures' in Jacob Neusner, Alan J. Avery-Peck (editors), The Midrash. An Encyclopaedia of Biblical Interpretation in Formative Judaism (Leiden: BRILL 2004), pp. 595-612

- ^David C. Jacobson, Modern Midrash: The Retelling of Traditional Jewish Narratives by Twentieth-Century Hebrew Writers (SUNY 2012)

- ^Adam Nathan Chalom, Modern Midrash: Jewish Identity and Literary Creativity (University of Michigan 2005)

- ^Craig A. Evans, To See and Not Perceive: Isaiah 6.9-10 in Early Jewish and Christian Interpretation (Bloomsbury 1989), p. 14

- ^Jonathan S. Nkoma, Significance of the Dead Sea Scrolls and other Essays (African Books Collective 2013), p. 59

- ^Encyclopaedia Britannica. article 'Talmud and Midrash', section 'Modes of interpretation and thought'

- ^Jacob Neusner, What Is Midrash (Wipf and Stock 2014), pp. 1−2 and 7−8

- ^Jewish Encyclopedia (1905): 'Midrashim, Smaller'

- ^Bernard H. Mehlman, Seth M. Limmer, Medieval Midrash: The House for Inspired Innovation (BRILL 2016), p. 21

- ^My Jewish Learning: What Is Midrash?

- ^ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA, Second Edition, Volume 14, pg 193

- ^ abENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA, Second Edition, Volume 14, pg 194

- ^ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA, Second Edition, Volume 14, pg 195

- ^ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA, Second Edition, Volume 14, pg 183

- ^(Genesis Rabbah 9:7, translation from Soncino Publications)

- ^Narratology, Hermeneutics, and Midrash: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Narratives from the Late Antique Period Through to Modern Times, ed Constanza Cordoni, Gerhard Langer, V&R unipress GmbH, 2014, pg 71

- ^1966-, Gafney, Wilda. Womanist Midrash : a reintroduction to the women of the Torah and the throne (First ed.). Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 3. ISBN9780664239039. OCLC988864539.

- ^1966-, Gafney, Wilda (2017). Womanist Midrash : a reintroduction to the women of the Torah and the throne (First ed.). Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 4. ISBN9780664239039. OCLC988864539.

- ^Kermode, Frank. 'The Midrash Mishmash'. The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^'Review of J. L. Kugel, The Bible as It Was'. www.jhsonline.org. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

External links[edit]

- Midrash Section of Chabad.org Includes a five-part series on the classic approaches to reading Midrash.

- Sacred Texts: Judaism: Tales and Maxims from the Midrash extracted and translated by Samuel Rapaport, 1908.

- Midrash—entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- Texts on Wikisource:

- 'Midrashim' . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- 'Midrash'. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- 'Midrash' . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

Midrash In English Pdf

- Full text resources

Midrash Tehillim English Pdf

- Tanchuma (Hebrew)

- Abridged translations of Tanchuma in English.

- Yalkut Shimoni (Hebrew)

Comments are closed.